Search for Double Beta Plus Decays |

|

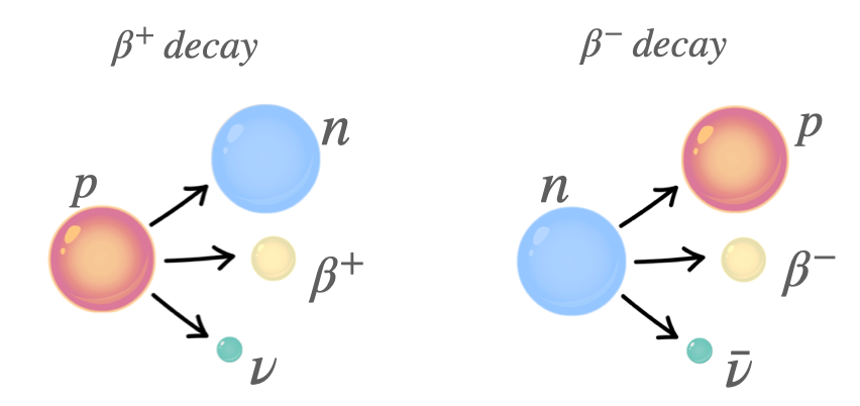

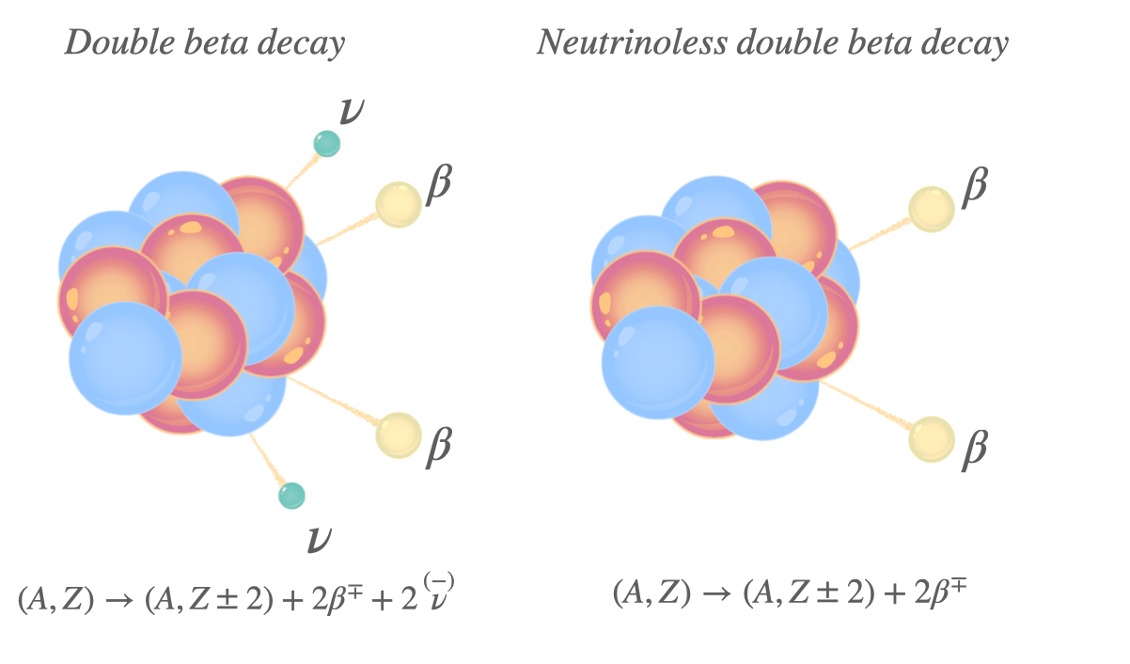

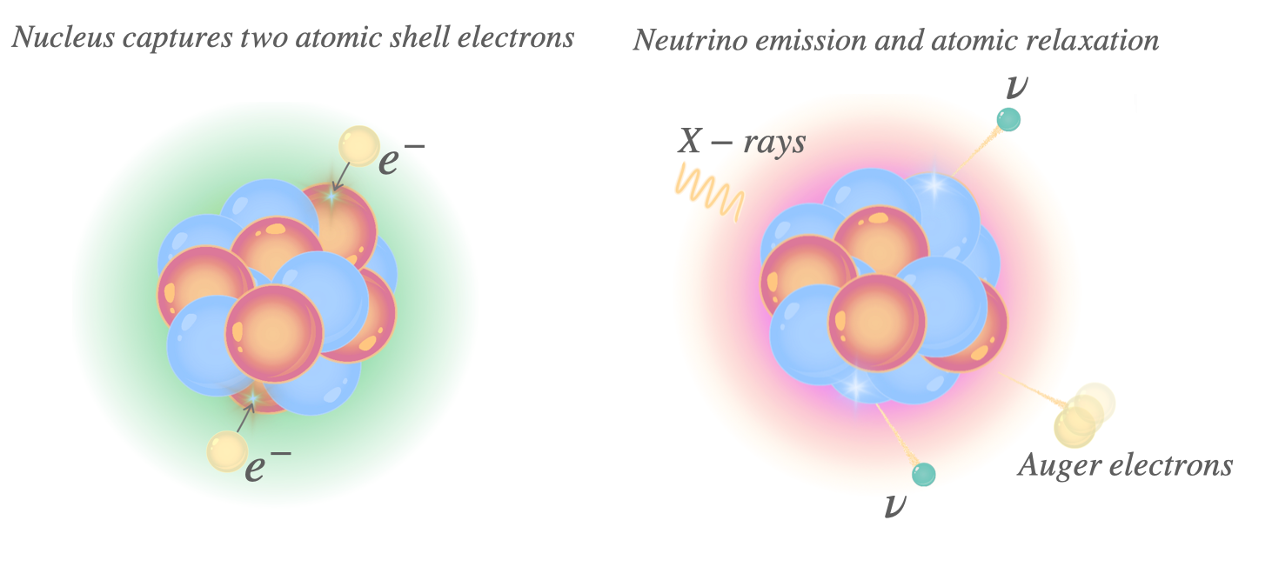

Understanding Double Beta DecayCertain isotopes are inherently unstable, causing their nuclei to break apart through nuclear decay. Imagine a nucleus as a tiny, densely packed space filled with positively charged protons and neutral neutrons. For an element to stay stable, the ratio of neutrons to protons must be just right. This delicate balance is why some isotopes are stable while others become radioactive. Radioactivity, as the name suggests, involves the spontaneous emission of radiation. An unstable atomic nucleus releases energy (carried away by emitted particles) to achieve a more stable state. There are various forms of radioactive decay, each involving the emission of different combinations of particles. One fascinating example of this transformation is double beta decay. It’s a rare process where an atom’s nucleus changes to become more stable. During this change, the nucleus emits two tiny particles (beta particles) and two almost invisible particles ((anti)neutrinos). A beta particle is essentially an electron or positron that’s emitted from the nucleus. Neutrinos are incredibly light, neutral particles that interact very weakly with matter, making them difficult to detect but they are crucial for balancing the energy and momentum in nuclear reactions.

Scientists like to study this because it helps them understand more about how the tiniest parts of the universe work. Double beta decay is extremely rare, with half-lives ranging from 1018 to 1024 years - far longer than the age of the universe, which is approximately 1010 years! This means that the atoms undergoing this decay do so very slowly. Observing double beta decay in a laboratory setting is challenging and requires highly enriched radioactive materials and advanced detection equipment. Physicist Maria Goeppert-Mayer first predicted double beta decay in 1935. The first indirect evidence of this phenomenon was reported in 1966 for tellurium in Japan and in 1967 for selenium in a collaboration between the MPIK Heidelberg and the State University of New York. Its direct observation was achieved only in 1987 when scientists Steven R. Elliott, Alan A. Hahn, and Michael K. Moe successfully detected it in a sample of selenium-82. Modes of Double Beta Decay

A lot of work has gone into studying the process, where two electrons are emitted, and the nucleus changes by converting two neutrons into two protons, increasing its charge by two units. However, this is just one part of the story. There are other intriguing modes of double beta decay that decrease the nuclear charge number:

Among these, only double electron capture (2ν2EC) has been observed while the others remain elusive.

Research into these decay processes is driven by advances in our understanding of the underlying physics that governs double beta decay. Data from double beta decay experiments help refine our theories about nuclear structure. Scientists are particularly excited about the possibility of observing neutrinoless positron-emitting processes. These could allow researchers to test and differentiate between theories beyond the Standard Model of particle physics, potentially uncovering new physics by revealing signs of lepton number violation. Unraveling these elusive decay processes might just turn out to be the key to unlocking the universe’s best-kept secrets - one particle at a time. The NuDoubt++ Experiment in a NutshellThe NuDoubt++ experiment is focused on exploring a very rare nuclear process called double beta plus decay, which involves the release of two positrons (particles similar to electrons but with a positive charge). Detecting this decay is quite difficult due to its rarity, the challenging nature of its detection, and the scarcity of suitable materials for study. To overcome these challenges, we propose a unique detector that combines advanced technologies to improve the chances of identifying these rare events. What We Aim to AchieveWith our new detector, we expect to identify double beta plus decay events after just one week of operation with one tonne of material. Moreover, we hope to greatly improve the detection limits for an even rarer process known as neutrinoless double beta plus decay. Why It MattersThe search for neutrinoless double beta decay is crucial because it could reveal whether neutrinos (particles that are everywhere but hard to detect) are their own antiparticle. Current experiments have set impressive limits, but to answer this big question, we need to make even more sensitive measurements. This requires larger experiments with better energy resolution and cleaner detection methods. Our NuDoubt++ detector is designed to meet these needs. The NuDoubt++ PrototypeWe propose to build a cylindrical detector prototype that uses about one metric tonne of a special scintillator material (a substance that emits light when it absorbs particles). This material helps us to distinguish between different types of particles based on how they emit light. The detector is equipped with advanced light sensors to measure energy and position precisely, allowing us to test our particle discrimination methods. Our GoalsOur detector is designed to measure rare double beta decays and set new limits for these processes. We are particularly interested in studying isotopes like Kr-78, Xe-124, and Cd-106. If we succeed, it would represent the discovery of some of the rarest decay processes known in physics. Eventually, we plan to use this prototype in an underground facility to search for these rare decays with even higher sensitivity. How Our Detector WorksHybrid Scintillator: This technology uses the ratio of two types of light (Cherenkov and scintillation light) to distinguish between particles. Massive particles produce less Cherenkov light, while positrons produce less Cherenkov light compared to electrons. Opaque Scintillator: This technique confines light within the detector, allowing us to collect detailed information about where and how particles interact with the detector material. This helps us to differentiate between electrons, gamma rays, and positrons. By combining these two techniques, we enhance our ability to reject background signals and accurately identify the rare decays we are looking for. Advanced Light Collection: We use Optimised Wavelength-shifting optical fibers (OWL-fibers) to improve light collection efficiency. These fibers are designed to capture more photons, enhancing the performance of our detector. Initial tests show promising results, and we are continually working to improve this technology. Stay tuned for more updates and results from the NuDoubt++ experiment as we continue our research and development efforts! GlossaryElementary particle - An elementary particle is a fundamental building block of matter that cannot be broken down into smaller components. Think of it as the tiniest piece of a puzzle that makes up everything around us. For example, electrons and quarks are elementary particles that combine to form atoms, which in turn make up all the objects and substances we encounter daily. Antiparticle - An antiparticle is like a mirror image of a regular particle. It has the same mass as its counterpart but opposite electrical charge and other properties. For example, if you have an electron with a negative charge, its antiparticle, called a positron, has a positive charge. When a particle meets its antiparticle, they can cancel each other out in a burst of energy, a process known as annihilation. Neutrino - A neutrino is an almost invisible particle that is extremely difficult to detect because it rarely interacts with other matter. It has no electrical charge and a very small mass, making it elusive and able to pass through most materials, including the Earth, almost undisturbed. Neutrinos are produced in large numbers in processes like nuclear reactions in the sun or nuclear reactors. Cherenkov light - Cherenkov light is a type of light that is produced when a charged particle, such as an electron, travels through a medium (like water or glass) faster than the speed of light in that medium. This causes a shockwave of light, similar to a sonic boom, which appears as a faint blue glow. It’s commonly observed in nuclear reactors and used in particle detectors to help identify high-speed particles. Scintillator - A scintillator is a special material that emits flashes of light when it absorbs particles. This light can then be detected and measured to determine the presence and energy of the incoming particle. Scintillators are used in various scientific and medical applications, such as detecting radiation in cancer treatments or in experiments to explore fundamental particles. Optical fiber - An optical fiber is a thin, flexible strand made of glass or plastic that transmits light from one end to the other. It's like a super-thin pipe that guides light, allowing it to travel long distances with minimal loss. Optical fibers are used in many technologies, including internet cables, medical instruments, and lighting systems, to carry information or light efficiently. |